dexamethasone and adriamycin. Results were bad, the median survival was around two years. In the 1990s something good happened; thalidomide …

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a B-cell malignancy with an inferior prognosis in comparison to other lymphomas. Most patients present with advanced disease and have short-lived remissions following CHOP-like chemotherapy. Exciting developments in recent years regarding disease biology and emerging therapeutic alternatives are changing the status quo of MCL. While there is no single best therapy for young and fit patients, dose-intensive regimens following autologous stem cell transplant and rituximab maintenance are currently considered standard of care.

Real-world data is important to compare the findings of clinical trials to population-wide outcomes. In a recently published study by Alexandra Smith and colleagues in the British Journal of Haematology, the authors analyze data from patients with MCL treated by the Haematological Malignancy Research Network in the UK (www.hmrn.org) spanning 2004-2015.1 Three hundred and ninety-nine patients were included with a median age of 74 years with a variable age range (36-96), and a male/female ratio of 2.96 with a widely heterogeneous presentation from indolent disease to the aggressive blastic variant (with an incidence of 16.4%). These findings reveal a very heterogeneous disease in its epidemiology, biology and thus therapies used, complicating retrospective data interpretation. However, in spite of its limitations, this paper presents valuable findings including a high number of patients with a relatively infrequent neoplasm treated outside of a clinical trial with long-term follow-up.

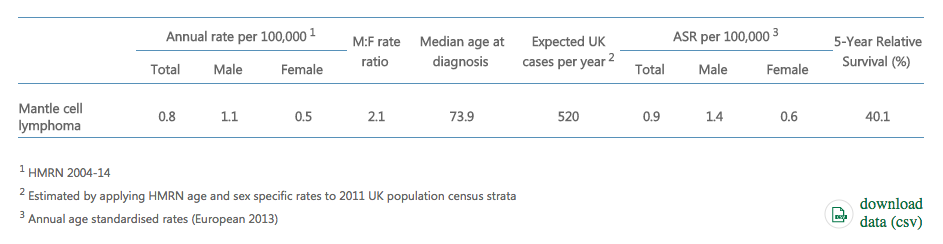

MCL incidence in the UK

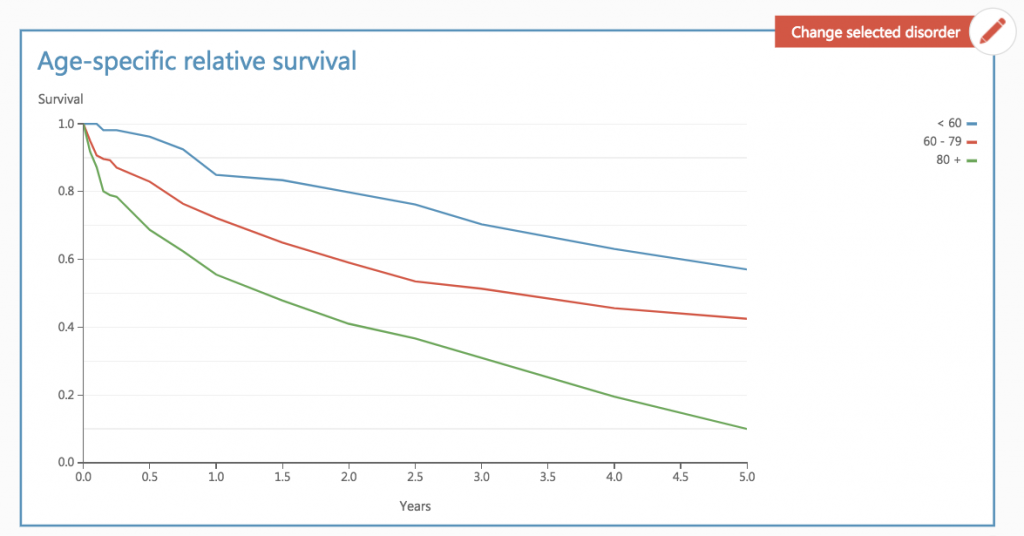

Almost half of patients died from their disease within three years of diagnosis. Outcomes were better for those who received chemotherapy plus rituximab vs. rituximab alone. After 2008 younger patients increasingly received regimens containing high-dose cytarabine. Only 8.1% received chemotherapy plus ASCT as consolidation for a number of reasons and had the best outcomes with a 3y OS of 85.5%, being younger with a better ECOG score. Patients who received high dose cytarabine (with or without ASCT) had a 3y OS of 76.8% which persisted after accounting for age. Fludarabine-based regimens were used in 2004-2006 and abandoned afterwards; bendamustine was introduced in 2012 and accounted for a third of first line therapies in 2014/2015. Median overall survival increased from 2 years in 2004-2011 to 3.5 years in those treated in 2012-2015. Median survival for n=140 patients who received second line therapy was poor (0.8 months). As in the fist line setting, changes for relapsed/refractory patients also occurred with the advent of ibrutinib and bendamustine, increasing 1-year OS from 32.1% in 2004-2011 to 50.5% in 2012-2016. Patients treated with ibrutinib were older but had the best outcomes regardless of age.

HNRM mantle cell lymphoma survival rates adjusted by age

These data are also relevant for the developing world; cytarabine is an inexpensive drug which is widely available, although intensive regimens which include Ara-C come with the need for hospitalization for chemotherapy administration and its complications such as neutropenic fever and transfusion requirements, which can be complicated for resource-limited settings to say the least. The same can be said for ASCT in the first line, except that it can be undertaken in an outpatient basis with modifications in the conditioning regimen. For these reasons, in our center ASCT in first remission is currently the norm for eligible patients. On the other hand, the transition to dose intense regimens which include cytarabine has been met with less excitement. It would be interesting to see a similar study to Smith et al. (or at least a single center comparative retrospective study) in a different setting, evaluating the benefit of dose-intense regimens in another socio-economic context. Unsurprisingly, there is little information available on MCL outcomes in the developing world, being an area of considerable interest.2 On the other hand, ibrutinib has proven very useful for elderly patients in the UK, with lenalidomide and venetoclax undoubtedly in the near future. These strategies are unfortunately less relevant for the developing world due to their enormous cost, with bendamustine and bortezomib being considerably more affordable, particularly the latter, as generics are now available for use in Mexico, making proteasome inhibitors an available route for abandoning chemotherapy-only regimens that have limited efficacy. MCL may be a good example of a disease where treatment will certainly differ according to resources available, but can evolve in different directions and must certainly not remain the same.

dexamethasone and adriamycin. Results were bad, the median survival was around two years. In the 1990s something good happened; thalidomide …

While acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients have a chance for long-term remission and cure, some of them will not attain …

Around 80% of children with ITP are disease-free within 1 year; a watch and wait strategy is considered standard for …